DISCOVER ROMANESQUE: Pictorial and sculptural decoration

Pictorial and sculptural decoration

In the absence of the great portals typical of French cathedrals and northern Italy, either sculpted or preceded by prothyra, sculptural decoration was restricted to Lombard band corbels in the exteriors and to capitals (often ancient or neo-ancient) in the interiors. Starting from the second half of the 12th century, narrations would unfold onto lintels and presbyterial furnishings, mostly pulpits and baptismal fonts. In a subsequent period, decoration would focus onto open-dwarf-gallery façades, after the Pisan cathedral model at first and, later, following the example of Lucca cathedral, under Guidi household’s workers.

Sacred stories were depicted in great polychrome groups sculpted in wood as well as in paintings covering the walls, now got lost, almost anywhere.

Province of Lucca

In the Middle Ages, the appearance of medieval sacred buildings in Lucca diocese and related areas was sensibly different from the present, not only with regard to changes in the architectural structure, but also to the substantial modifications in the sculptural and pictorial decoration as a whole, which, in most cases, got partially dismantled, musealized or even totally lost.

In the first place, pictorial wall decoration was often subjected to 19th-20th-century restoration works that, due to a distorted vision about the supposed appearance of a medieval church, stripped plaster off the masonry to take it back to natural stone. In contrast, churches were often vibrant with colours, as confirmed by fragments of frescoes found in the churches comprised in our itineraries, as in many other ones in the territory. This is the instance of decorations of the pievi of Valdicastello – either the late-14th-century apsidal decorations and those (maybe earlier) of the aisles, which have left a few sinopias – and of San Pantaleone in Pieve a Elici. Among the few still conserved exemplars, the territory hosted the most illustrious and ancient decorations of S. Frediano basilica in Lucca, of the Pieve of Sesto di Moriano and of the badia of Cantignano. Along with wall paintings, many local churches guarded mobile painting works, mainly represented by painted crosses in two iconographic versions: Christus Triumphans, portrayed alive and vanquishing death (as in the case of the most important, well-known, sculpted cross found in the area, the Holy Face kept in S. Martino cathedral of Lucca, making the object of a special devotion in the Middle Ages) and the modern version of Christus Patiens, where Christ is depicted at the time of his passion and death. A 13th-century exemplar of the second type is guarded in the Pieve of S. Giorgio di Brancoli.

The rich sculptural decoration has been more extensively conserved. Indeed, architectural elements such as frames, lintels and capitals were often sculpted, sometimes as an imitation of ancient models, or they directly reused pieces from the Classic age. On the contrary, presbyterial fittings, represented by a chancel in marble slabs and a pulpit, often got lost despite of their rich sculptural decoration, as in the case of the 12th-13th century example that is still visible in the Pieve of S. Giorgio di Brancoli.

Province of Pisa

Pisan religious buildings show a rich sculptural repertoire: Lombard bands on façades and apses are decorated by symbolic, geometrical, vegetal, human and anthropomorphic motifs, sculpted in stone by specialized workers travelling throughout the territory.

Lupeta and Vicopisano churches present a few sculpted slabs on their façades, featuring biblical scenes reflecting either clients’ and workers’ specific decorative and narrative taste.

Now largely altered by subsequent changes and restoration works, pievi interiors were formerly decorated by frescoes. Significant traces of pictorial cycles dating from the 13th century are found in Vicopisano pieve as in Volterra cathedral (dating from the 14th century); on the contrary, other paintings got lost, such as the one made by a few apprentices of Giotto’s school, once decorating the choir and the church walls of Volterra badia.

Among sacred fittings, the baptismal font of Calci was richly sculpted by hands of Biduino’s workshop; the pulpit of Volterra cathedral is attributed to Guglielmo’s school and may be dated from the 12th century.

A few major instances were left as to polychrome wooden sculptures. In particular, the Depositions in Vicopisano pieve and Volterra cathedral are worth mentioning. Both groups, similar as to their composition and dating (13th century) are attributed to workers travelling throughout the territory, who also signed the works found in Pisa cathedral and in San Miniato.

Sardinia

The panorama of sculptural and Pictorial decoration between the 11th and the 14th centuries appears to be relatively poor of evidence, as only sporadic and fragmentary facts were left. Most rare instances of sculpture, unrelated to architecture, are available. Yet, there is a rich series of decorative elements applied to corbels, Lombard bands and external wall faces of churches. The few works that are worth mentioning certainly include the Pulpito di Guglielmo, received by Cagliari cathedral in 1312, but made between 1159 and 1162 for the Primatial church of Pisa. Sculpture, in bronze, is also related to two objects mentioned in sources, which have arrived to our days. The first is guarded at the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Cagliari: it is a jug coming from Mores, featuring a peacock, referable to the 11th century, of Ispanic-Moresque manufacture. The second is a pair of knockers, still in bronze, coming from the cathedral of Oristano, dated 1228 on an epigraph reporting also the author’s name, Placentinus, as well as the clients’ names, the ‘Judge’ Mariano II of Arborea and the bishop Torgotorio de Muru. Until a few years ago, the only instance of pictorial decoration of churches was represented by the cycle found in the central apse of the Santissima Trinità di Saccargia, in the countryside of Codrongianos, dated from the second half of the 12th century. Paintings were also brought to light during restoration works at the church of San Pietro a Galtellì, which recent studies date from the early 13th century, and in San Nicola di Trullas, in the countryside of Semestene, still dating from the 13th century. The 14th century has left the cycles of Nostra Signora de Sos Regnos Altos in Bosa and of Sant’Antonio Abate in Orosei, as well as the paintings of the San Pantaleo in Dolianova, dating between the 13th and the 14th centuries. A few mobile works of art refer to the same period. The 13th-century Deposition now conserved in the parish church of San Sebastiano in Bulzi is composed of five wooden polychrome statues; in the same way, a noteworthy painting on wood, formerly attributed to Memmo di Filippuccio, is now kept at the Archbishop’s Palace of Oristano, although it was anciently hosted in the crypt of the Basilica of Santa Giusta.

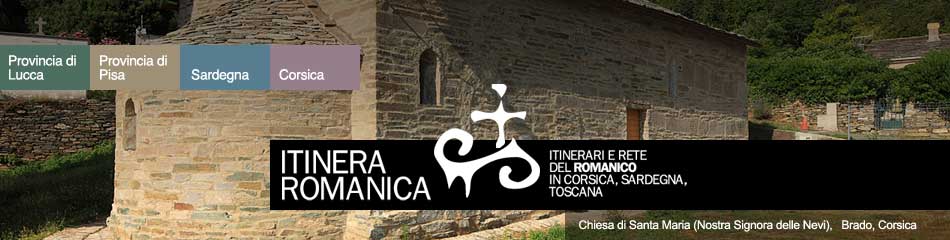

Corsica

The Romanesque churches of Corsica are also marked by the sobriety of their decoration: blind arcades springing from modillions, polychrome ceramic bowls (called bacini) as well as geometric, phytomorphic, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures, mostly sculpted in flat-, bas- or full relief.