Stone connotes the whole architecture of the Upper Tyrrhenian, laid in increasingly large and regular ashlars as excavation and working skills were being recovered. Almost to highlight the executive accuracy and the preciousness of the material employed – in the lack of marble, using white or pearl-grey limestones, or golden sandstones – wall faces often renounced any sophistication or sculptural decoration. At the same time, the great construction of Pisa cathedral – a crossroads of Mediterranean, Arab and Byzantine echoes – spread a different taste for colour: blind arcades, sometimes resting on columns or pilasters, at times including smaller arcades, gave surfaces a movement effect; they were run through by brickbands, obtained in each territory by using local green, reddish, grey stones, with the insertion of coloured inlays and lozenge decorations.

Province of Lucca

Medieval architectures of Lucca show a prevalence of white limestone, verrucano and litharenite, the first one being easily found in Monti Pisani, the latter in the Apennines.

Verrucano and litharenite prevailed in the early Middle Ages, at first simply broken and combined in an irregular masonry, mixed to river pebbles in the oldest instances and sometimes enlivened by earthenware insertions, later cut in ashlars installed in regular courses.

Only since the 11th century, according to a new architectural taste, would white limestone dominate the scene; identical to marble as to whiteness and purity, it was worked in a sophisticated way: ashlars were cut in regular parallelepipeds, their exposed surface made even and polished; they were placed in alternating courses of different height, creating an outer texture often recalling ancient techniques.

Chromatic effects were obtained, again, by mining grey and black limestones from Monti Pisani and, in late 13th century, using the red type of Garfagnana and the green type of Prato.

Province of Pisa

Different material qualities were employed in the Pisan territory: ceroid limestone, i.e. ‘San Giuliano’s marble’, calcarenite, commonly called ‘Verrucano’ as it was quarried from Monte Verruca, green and violet schists, rubble from Caprona, panchina volterrana, Pignano tuff.

These names underline the local origin of the materials used in medieval construction yards. Indeed, stones were often quarried in the surroundings, in order to cut processing and transport costs, which were very high in that age. Stonecutters, then, used to rough out materials right in the quarry, prior to taking them to their working place.

In Pisa, the skill to use specialised building techniques was reintroduced (if it ever got lost) earlier than in other Italian areas. Thanks to such skills, the majority of churches in the region was built in dimension stone, installed on horizontal courses, using only a little mortar, if any.

In the areas of Pisa, Lucca, Sardinia and Corsica, building masters engaged in the construction of the cathedral spread a few formal modes, such as dichromatic wall faces and lozenge motifs on the façades.

Sardinia

The extent of Romanesque in Sardinia is essentially given by the true impressiveness of the phenomenon within the building framework: over 150 churches, quite intact, still today representing one of the most distinctive features of the historic landscape of the island. As anywhere, the Romanesque concept in Sardinia is linked to the concept of stone, rather than to workers’ style, resulting from the cultural variety of their itinerating construction yards. Apart from two churches, completely built in brickwork, the material used is stone, cut into blocks dressed and installed with accuracy. Local colour is determined by soil variety: warm-hued limestone to the north, in the basilica of San Gavino in Porto Torres; golden sandstone of Sinis in the cathedral of Santa Giusta; most dark basalt in Santa Maria del Regno, palatine chapel of Ardara, chief town of the Giudicato (kingdom) of Torres; similar volcanite in the Camaldolese abbey of Santa Maria in Bonarcado; still volcanite, here of a red type, quarried from the plateau of Ghilarza, in the San Pietro di Zuri; chromatic plays of limestone and basalt in the wall face of San Paolo di Milis; red or black volcanite, regularly alternated to limestone or lighter-coloured volcanite in the dichromatic courses of San Pietro di Sorres, San Pietro del Crocifisso in Bulzi and Santissima Trinità di Saccargia. Only a restricted group of churches in Gallura is built in granite; in San Simplicio, Olbia, the exceptionality of this lithic material matches the equally rare occurrence of brickwork.

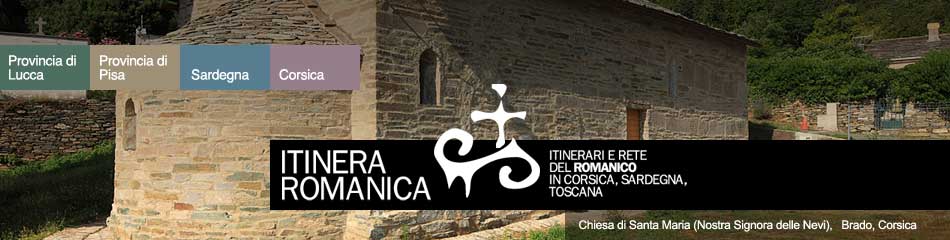

Corsica

The diversity of building materials used in Romanesque churches of Corsica – granite, limestone, schist, cipolin – reflects the geological diversity of the island.

Indeed, raw materials mainly come from nearby quarries. The polychromy of some buildings is obtained by combining some of these materials. Roofs are made in schist slates or hollow tiles.