The institutional relationships between mainland and islands corresponded to an increase in trade exchanges, conveying not only goods, but also men and art technologies. Once settled in the various territories, workers adjusted their training principles on the basis of their client’s demand, based on the availability of different materials and tools. As a result, a common language originated, along with a variety of architectural forms, deriving from the contribution of distinct professional figures – stonecutters, sculptors, carpenters, masons and painters – concurring to achieve a homogeneous architectural environment.

Province of Lucca

Starting from the 11th century, a number of Romanesque churches witnessed the fortune of Lucca, in conjunction with the general ‘awakening’ involving the western world. Under the episcopate of Anselmo da Baggio (1057-1073), later pope under the name of Alexander II, various churches were rebuilt or founded ex-novo, such as the cathedral of San Martino, San Michele in Foro and Sant’Alessandro, marked by a basilical layout and a sober classicism inspired by the austerity of the Gregorian Reform, promoted by the bishop of Lucca. This return to the ancient style assumed specific features, allowing to identify a ‘Romanesque of Lucca’, marked by distinctive traits that would last until the 13th century: the persistence of Greek and Roman tradition, lack of vaulted ceilings, domes and matronea, a geometric conception of space and the exclusive adoption of the basilical plan. The archetype is probably the church of Sant’Alessandro, whose model is reflected by the pievi of Diecimo, Valdottavo and Versilia.

Province of Pisa

Between the late 10th and the 12th centuries, Pisa went through a thriving economic and social age, which scholars called Romanitas pisana, being the town’s ambition to become a novel Rome. It renewed its architecture, employing considerable resources and importing skilled workers from the East, a land with which it had special trading and cultural exchanges.

In 1063, the construction of the cathedral led to the adoption of a strongly innovative language on the Italian architectural panorama. Originally set by the architect Buscheto as a temple in white marble, inspired to the Classical age, the building was subsequently reworked to comply with the features designed for the baptistery by Deotisalvi, a new architect on the market. Therefore, the longitudinal body of the cathedral was enlarged and the façade was put forward by adding a few bays.

The baptistery building was started in 1153, followed by the construction of the tower in 1174, marked by a circular plan and an uncommon open-dwarf-gallery motif.

The architectural style of the cathedral square would soon become a model to be exported, in a reduced scale, on the territories subjected to Pisan influence: pievi, abbeys and subordinate churches were renovated according to the modes introduced on the market by specialized travelling workers.

Clients were represented by bishops and noble households, aspiring to convey the image of a powerful, rich town by means of sacred architecture.

Sardinia

Archive documents report that, after the first half of the 11th century, Sardinia was divided into four kingdoms, called Giudicati. Each of them was headed by a king, or ‘Judge’, holding supreme powers. Each Kingdom was divided in curatorie, corresponding to the ecclesiastical partition into dioceses. The territory was militarily defended by castles, built on hilltops. The population gathered in coastal cities and numerous villages scattered throughout the territory, depending on churches. The largest ones were cathedrals and abbeys; other churches, such as parish or monastic churches, were subordinate to them. Until the early 14th century, Romanesque architecture flourished mostly along the coasts and in the fertile plains of the western half of the island. The eastern region, being mountainous and lacking wide plain areas suitable for an intensive exploitation of agro-pastoral resources, had few towns and, as a result, few Romanesque churches, even in the countryside. Churches were mainly concentrated in the western plains, from Logudoro to Campidano where, still today, they stand as a landmark in the island landscape, either urban and rural. When inserted in a town context, they act as the hub of an often intact medieval system. When standing alone in the countryside, they witness the ancient existence of a village by now abandoned. Much more than medieval castles, mostly reduced to ruins, Romanesque churches represent at the best the remains of a past age, when the Island was able to express an architectural civilization at the European level.

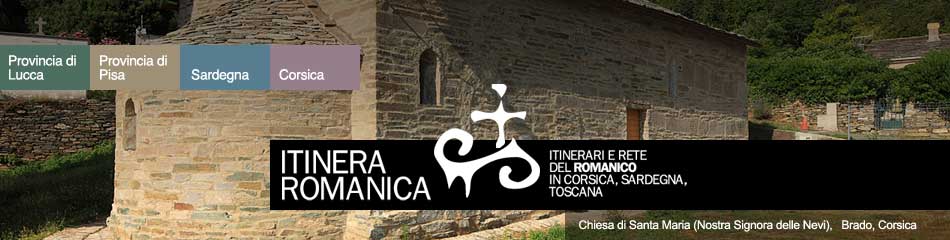

Corsica

The Corsican Romanesque heritage includes more than two hundred churches, built between the 11th and the 13th centuries, at the same time of the administration reorganization of the Church and the ecclesiastical reform.

Their architectural features make them similar to Tuscan and Sardinian ones, an evidence of the circulation of men and models at the heart of western Mediterranean.